“HUB TREES” – Cicle Artistes Sant Cugat 2017

(CAT) Tota la meva obra és un intent de connexió o re-connexió amb la natura i amb tot allò que ens envolta. Pretenc posar en relleu la seva bellesa , els seus valors intrínsecs, així com convidar a reflexionar sobre com ens hi relacionem.

La manera de viure de la nostra societat actual ens exigeix una activitat incessant i hem perdut l’hàbit de la observació de l’entorn més proper i immediat.

Voldria crear a través de l’art uns escenaris propicis per a qüestionar-nos la nostra relació amb l’espai i el temps, gaudint a l’hora d’uns entorns inspirats en la natura; amb la voluntat de sentir-nos més arrelats al món.

La professora d’Ecologia Forestal a la University of British Columbia (Canadà), Suzanne Simard, ha desenvolupat i contrastat diverses teories al voltant de com els arbres es comuniquen entre ells. Els seus treballs de recerca demostren que els arbres efectivament es comuniquen i que no es comporten de forma individual competint per la supervivència del més fort com apuntava Darwin en les seves teories, sinó que interactuen entre ells (network) ajudant-se per sobreviure.

A partir d’aquesta idea sorgeixen les dues peces/instal·lacions principals de l’exposició.

El concepte “Hub” està vinculat a diversos àmbits. En termes informàtics, un “hub” és un concentrador o dispositiu que permet centralitzar el cablejat d’una xarxa d’ordinadors per després poder-la ampliar. En transport, s’anomena “Hub” al punt d’intercanvi o centre de distribució de trànsit de persones o de mercaderies.

La paraula “Hub” per mi pren tot el significat quan es refereix a connexions, lligams, relacions, xarxa, intercanvi, etc.

(EN) “All my work is an attempt to connect or reconnect with nature and with everything that surrounds us. I intend to highlight nature’s beauty, her intrinsic values, as well as invite people to think on how we interact each other. The way we live in our current society demands an incessant activity and we have lost the habit of observing our closer and immediate environment. I would like to create through the art some scenarios that are conducive to questioning our relationship with space and time, enjoying nature-inspired environments; with the will to feel more ingrained in the world.

The Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia (Canada), Suzanne Simard, has developed and contrasted several theories about how the trees communicate with each other. Her research work shows that trees effectively communicate between them and that they do not behave individually by competing for the survival of the strongest, as Darwin pointed out in his theories, but interacting among them (network) by helping themselves to survive. From this idea the two main pieces / installations of the exhibition arise. The concept “Hub” is linked to various fields. In terms of information technology, a “hub” is a hub or device that allows the wiring of a computer network to be centralized and then expanded. In transport, it is called “Hub” at the point of exchange or distribution center for people or traffic of goods. The word “Hub” for me takes all meaning when it refers to connections, links, relationships, network, exchange, etc …

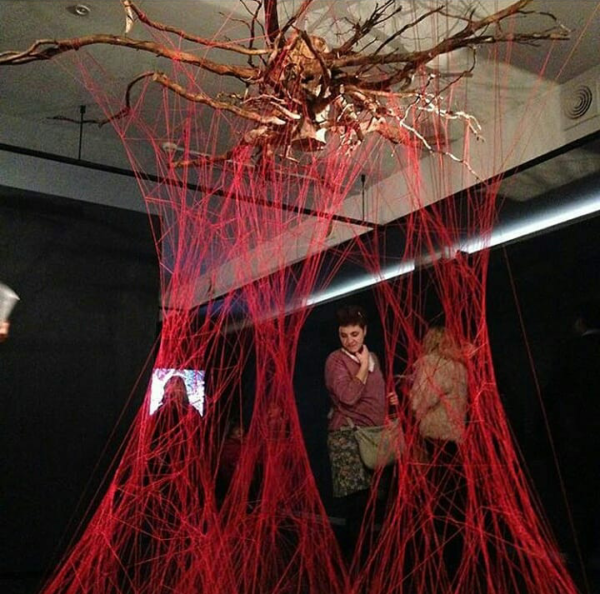

Instal.lació Hub Tree/Hub Tree installation

Instal.lació inspirada en el concepte de Hub Tree o també Mother Tree de la Suzanne Simard:

Arbre gran i vell amb una xarxa enorme (network) associada. És un arbre dominant al bosc, i està possiblement connectat a tots els arbres del seu voltant, fins i tot d’altres espècies.

https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_simard_how_trees_talk_to_each_other

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-8SORM4dYG8

Fruit del meu projecte #OneTreeaDay365days actualment disposo d’un arxiu de 365 imatges, amb els arbres com a protagonistes. En aquest projecte em vaig proposar donar-los visibilitat amb el simple acte diari i durant un any de fer-los una fotografia i penjar-la a Instagram @nuriabenetart. El primer dia del projecte va ser el 14 de gener del 2016 i la primera fase va finalitzar el 15 de gener del 2017. Aquest treball d’investigació i artístic alhora s’ha convertit en el punt de partida de tota una sèrie d’obres que es manifesten utilitzant diferents llenguatges. Moltes d’aquestes imatges han estat transferides sobre unes làmines molt fines de porcellana amb pasta de paper, utilitzant només pigments ceràmics negre i vermell. Amb el pigment vermell destaco tots aquells elements artificials (cables elèctrics, senyals de trànsit, faroles, etc..) que coexisteixen o conviuen amb els arbres i que conjuntament esdevenen el paisatge urbà.

(EN) As a result of my #OneTreeaDay365days project, I currently have a 365 file of pictures, with trees as protagonists, and giving them visibility. In this project I chalenged myself with the simple daily act and during a year of making a photograph of a tree and hanging it on Instagram. The first day of the project was on January 14th, 2016 and the first phase of the project ended on January 15th, 2017. This research and artistic work at the same time has become the starting point of a whole series of works which are manifested using different languages. Many of these images have been transferred on very thin sheets of porcelain with paper pulp, using only black and red ceramic pigments. With the red pigment, I emphasize all those artificial elements (electric cables, traffic signs, lanterns, etc.) that coexist with the trees and that together they become the urban landscape.

Audiovisual sobre Tapís/Projection on a Tapestry

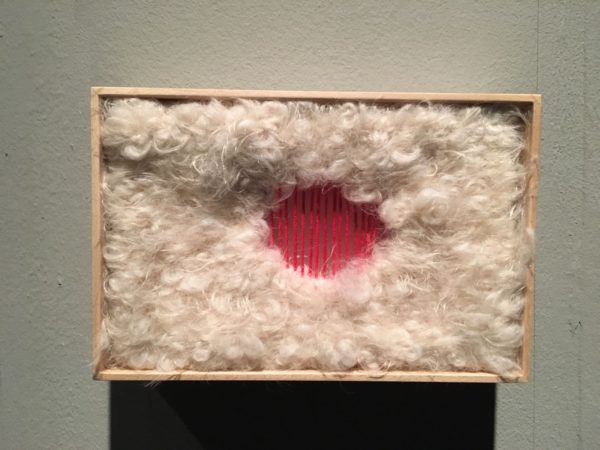

Exercici d’abstracció, aïllant de varies de les imatges de l’arxiu de fotografies del projecte #OneTreeaDay365days, el cablejat i altres elements que hi apareixien. D’aquest procés obtinc tot un entramat de línies que han estat traslladades en un gran tapís, en vermell.

El tapís esdevé la pantalla sobre la qual es projecten les mateixes imatges originals utilitzades anteriorment per abstraure el cablejat. Elements que coincideixen en un temps i espai determinat, es separen i es tornen a unir novament amb la projecció, establint d’aquesta manera un nou diàleg i discurs.

Les proves experimentals de tapís realitzades amb diferents materials i en petit format (17×9,5cm), formaven part de l’exposició acompanyant el tapís de grans dimensions.

Visites Guiades i comentades:

– Dijous 15 de febrer, 19h Inauguració i visita guiada i comentada

– Dissabte 24 de febrer a les 11h

– Dimecres 7 de març a les 19h

Taula rodona a càrrec de Marc Castellnou i Gerard Passola:

– Dissabte 10 de març a les 18h

Activitat Escoles i Instituts (contactar prèviament amb l’artista al 607.23.53.83)

Textos originals inclosos en el catàleg

LAUDATIO para NÚRIA BENET

Joaquín Araújo

La mejor definición de poeta es la más corta. Con solo tres palabras Federico García Lorca nos recuerda que la Natura escribe, sin cesar, poemas. Como se trata de La mejor artista también pinta, hace sonatas, edifica residencias, como los corales que son mucho más grandes que todos los edificios humanos de toda la historia. Eso sí, los arrecifes vivos tienen 250.000 siglos más que la primera arquitectura humana.

La Natura tampoco ha descuidado las caricias que el sonido puede darnos y por eso, ahí afuera, nos esperan las melodías menos conocidas pero las más leves y constantes. Pero si de esculpir se trata resulta que todo lo que vemos ha sido tallado por ese cincel del tiempo que es el agua. Incluso cabe añadir que los animales son los seres más danzarines y fotogénicos. Tampoco hay drama más complejo que la misma vida, ni teatro más grande que el derredor. En suma que el Arte nos precede en todas las disciplinas y con ingentes creaciones.

Lorca, como muchos de los mejores creadores, considera que crear es acordarse de lo creado y cursarle una amable invitación a participar en nuestras fiestas. El Arte, pues, como la Natura, es un surtidor de novedades, asombros y confluencias. Es forma, color, movimiento y lenguaje. Por eso afirmó: “Poeta es árbol”.

No fue el primero. Podemos rastrear aproximaciones a tan lúcida expresión en todas las épocas y en casi todas las culturas. Desde el magdaleniense reconocemos, de alguna forma, que la primera materia prima de toda disciplina artística es el derredor ya que proporciona los elementos básicos para crear. Todo paisaje, todavía vivo, es un alambique que destila el mejor licor, la inspiración, y lo hace con esa uva que es admirar lo contemplado.

Pero el primer reconocimiento explícito de este concepto es tan anciano como una de las primeras formas de escribir que conocemos. Me refiero al chino, al idioma que se expresa, sobre el papel, con ideogramas. Utilizar grafías que se aproximan a la realidad de lo nombrado consigue el más lúcido encuentro entre el símbolo y la realidad, entre lo expresado y lo impreso. De la misma forma que entre las palabras de nuestros idiomas y la realidad se interpone el abismo de lo simbólico y abstracto en los sinogramas se da, con frecuencia, un abrazo entre la forma y el fondo de la palabra, entre significado y significante, entre lo que sucede y lo que nombramos. Acaso donde mejor se aprecia tal sintonía es con el término vivir que se dibuja como una planta creciendo, sin duda la mejor aproximación posible a lo que mantiene y consiente nuestras vidas. Vivimos, en efecto, porque los vegetales crecen.

No consigo distinguir fronteras entre las diferentes destrezas del arte. Las palabras del pintor son la luz y las infinitas sorpresas que se esconden en su seno. Las del compositor son las notas, las del escultor lenguajes todavía más antiguos pues dormían, desde siempre, en la piedra, la madera o el mineral. Reitero que toda disciplina creativa procede de y como la Natura.

Cuando desembocamos en las aportaciones de Nuria Benet encontramos también estos esenciales vínculos. Es toda una confirmación de porqué la palabra arte, en chino, resulta casi idéntica a la palabra árbol, pero a la que se añade solo una tilde. Se reconoce, pues, que se crea a partir de la MATERIA/MADERA. Todo arte es recreación. Pero no menos tregua, oasis, declaraciones de paz y simbiosis, alianzas con lo mejor que nos queda de nosotros mismos. La Natura y el Arte desafían y, a veces vencen, al todopoderoso tiempo con sus ansias de eterna continuidad.

En las obras de Núria, como en los perdederos naturales, encontramos pausas, oasis en la arrebatada eficacia que hemos puesto en cegar la luz, obturar las transparencias, enterrar la tierra y amortajar la vivacidad… No es casual que el color de la ceniza impere en las muchedumbres y sus residencias. Pero sobre todo en los cielos.

Arte como el de Núria Benet restaura, en parte, tanta torpeza. Es luz limpia en medio del crepúsculo artificial que nos invade.

Coincide con lo que sucede en las arboledas que son fábricas de transparencia, asambleas de colores, templos de sonoridad, fondas de la vida más vasta y variada. Arte y poeta son árboles, no lo olvidemos.

En Núria Benet se fertilizan todas las confluencias señaladas. Su sobresaliente sensibilidad nos vincula a lo esencial. Nos recuerda la principal función del Arte: ser el mejor antídoto para esta loca enfermedad que supone el habernos arrancado del derredor; el estar acorralando al infinito y asesinando a las primaveras.

GRACIAS y QUE LA NATURA Y ARTE DE NÚRIA BENET OS ATALANTEN.

Oak, ash, and tamarind

Vince van Geffen, Barcelona, 2017

An appreciation of the work of Núria Benet

Are we still part of nature? If so, to what amount? Which part of us acts in response to the soft quivers of the soil we tread on, in response to a fierce storm blowing, to the whispering leafage, or to rock flaring up in seconds of sudden anger? And how can this portion stand fast against a brutish background made up of the incessant blare of industry with no more than paper-thin vitrified clay, bleached roots and branches, aquamarine sponges, or coagulums of spattered paint?

And, are we to stay together, reworking our feeble coexistence, or are we to grow further apart, separating altogether perhaps?

The work of Núria Benet could be summarized, I believe, with a single question: What is our relationship with Nature? It may present itself to us in a variety of forms, such as ceramics, photography, carpets, or even an uprooted tree, yet all of it leads to this specific enquiry.

Shape is the artist’s answer of course. To reformulate, to try and be more precise, to see the problem anew, unmarked, as if for the first time, to find a new form for it again and again; that is the artist’s occupation. It is his or her privilege and at the same time a test of ability. And there is, and should be, no beyond. The question answered would be its demise.

Núria’s question is universal. Art, religion, philosophy, as well as science, are bent over this question since their beginning. There is no doubt why. The large power we spring from, and will return to, seems oblivious of our consciousness. Its overwhelming force sweeps us aside. Its indifference for our fate hurts us. Its communications seem not to be aimed at us, and yet we have no other choice but to try and follow these mysterious directions. Each culture has posed this question. And every individual, at one point of its existence, has been confronted, in awe and wonder and fear, with Nature’s supremacy.

It is no surprise that Núria has singled out the tree as a vehicle for her views. The tree is a common go-between. It connects us with the deeper layers of the natural world. It ties us to Nature’s more profound workings. It unites us to our true origins. And it can do so because of its stature and its condition.

On one hand the tree reflects us with its vertical appearance, crowned with a sphere. As we humans do, it stands tall among other species. But on the other hand its roots not only condemn it to a fixed place, they also enable it to form part of a larger world of veins and rock and subterranean flow, of covert announcements, whispered in tremors we are not privy to. While we are free to roam the Earth’s surface, free to undertake as we imagine, we pay for our abilities with the lack of a true bond with our environment.

Because of its shape and position, the tree is often regarded as a point of connection. In our more reflective moods, when we question our existence, we turn to one of Nature’s most affable manifestations for an answer. As no other natural expression the tree involves us in its realm.

And yet Núria´s tree should not be regarded solely as the soft machinery that breathes light, releases sugar, and performs photosynthesis, as the overall winner in the competition for sunlight, as one of the elements figuring in Linnaeus´ Imperium. We should think of a more metaphysical task for her trees as well.

Through history trees could perform such a task because of their verticality, a shape that suggests a connection between earth and heaven. Towering high above us and writhing deep beneath us, they are regarded as places of transmission.

Reverence of trees takes place all over the world. Its shadowy canopies, inhabited by shy nymphs, provide cover for rituals, for sacred believes honoured by ceremony and sacrifice. Thronged together in groves, under foliage so thick that sunlight is denied, wind annulled, sound excluded, they create the necessary atmosphere for supplication. The Gods need some encouragement to grant us favours.

No Hindu shrine is complete without a tree, either papal or banyan. There are the justice trees on Eastern Europe’s village squares, often linden, that witness the passing of judgement. The Buddha achieved enlightenment under a large fig tree, significantly called the Ficus religiosa. The oak in the Druid’s garden throws it shadow on Celtic rituals, while in the tropical belt the tamarind is the Goddess in disguise, showing her benevolence in an abundance of fruit. Elsewhere man aspires to pacify a tree’s spirit, thus ensuring the crops, commemorating the dead, adverting illnesses. Or else he regards them as shrines where to leave objects to soak up divine blessing.

Núria too approves of tree ritual. A year long she goes out in the morning, day after day, and takes a picture of a tree.

There are ideas that are shaped like trees, such as the World Tree, or Axis Mundi; the gigantic ash that supports the heavens. Or the Tree of Knowledge whose forbidden fruit caused the fall of man. There is the Tree of Life that unites all forms of existence, which represents the great chain of being, the scala naturae that takes us downward from God all the way to the inert mineral.

Núria´s Mother Tree surely seeks a place among such conceptual species. Her tree may well be inspired by Suzanne Simard´s investigation into the beneficial flows of carbon from a so-called Hub Tree to its seedlings, and the exchange of nutrients between trees in what appears to be a quiet subsoil economy, but it takes this marvellous example further and transforms it into a model for society. With its stem clad in hand-shaped paper, its cotton filaments crossing the pavement, its tea-lights stirring in the breeze, it functions as an external soul. Núria regards the benevolent actions of the Mother Tree, dispatching nutrients where they are most needed, coming to the aid of saplings, as an inspiring example of how society should work. Trained in classical economics, a milieu where someone’s gain means another one’s loss, she is astounded by the compassion that rules these forest economics. Did Schopenhauer not say that compassion is the basis of all ethics?

Well then, it is this that needs to be transmitted, that needs to be cast in form, that needs to be repeated in every technique available. And so she creates a panoptical world that is made up of such things as an animated carpet, brought to life with projection, wafer-thin ceramics etched with images, hubs where one is ritually filled with additional energy, three hundred and sixty-five tree pictures on Instagram, and recently, a stump and polished roots, hung in space.

instagram #nuriabenetart

instagram #nuriabenetart